They could certainly be described as possessing a poster-like quality in terms of their size, bright colours and clear, almost austere formal idiom. However, it isn’t immediately clear what exactly the 15 polychrome woodcuts from the Norwegian printmaker and sculptor Are Andreassen are about.

Røst is the title of his series of prints and also the name of a group of islands along the outer edge of the Lofoten, which lie as far as 100 km off the coast of the Norwegian mainland.

Especially well-informed viewers may perhaps know what took place up there almost 600 years ago: in 1432 three Venetian merchant ships set out from Crete for Bruges. A storm blew these ships, which were under the command of Captain Pietro Querini, extremely far off course and then destroyed them. The survivors, who included the captain, became stranded on Røst, where they were taken in by local fishermen. In his memoirs Querini enthusiastically describes the close bond with nature manifest in their way of life – as well as their hospitality and, above all, the production of stockfish (i.e. fish, particularly cod, preserved through drying): the hit Norwegian export, which he popularised in Italy following his return.

Every year a festival based around Querini’s story is held there, and every third year there’s even an opera performed about it. In 2017 Andreassen was invited to Røst to occupy himself with this place and its history and collect material for an exhibition. He’s also an islander himself, his home is in the polar circle, too, and isn’t really that far away. The artist, who has seen a lot of the world, is originally from Tromsø and now lives and works on Fleinvær – where he is one of the few permanent inhabitants.

Exhibition on Røst, Fischfabrik Glae N556, 2018 and Are Andreassen (right) at the opening on Föhr, Museum Kunst der Westküste, 2023, photo: Lukas Spörl

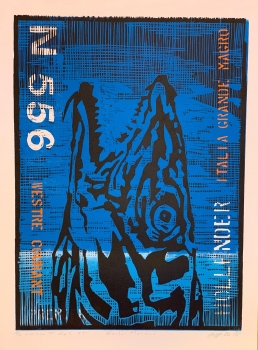

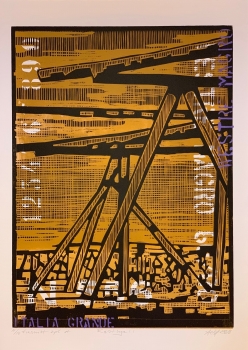

With the woodcut, Andreassen uses a reproduction medium that is very contemporary in the sense of his motifs: it is the oldest artistic printing technique that emerged at the beginning of the 15th century. However, his prints don’t show the historical events themselves. There are no wind-whipped ships, no moment when they threaten to go under, no rescue of the survivors. What we see is the Atlantic cod, which made Norway rich and whose export – along with other marine species – still continues to furnish this country with exceptional profits. In smaller coastal villages, the drying process still involves the use of traditional fish flakes as well as the “Råvedstenger,” the wooden bars named after the square sail of Viking ships.

People settled on Røst and hundreds of other very distant islands off the northern coast of Norway more than a thousand years ago. Here, they were close to rich fishing grounds for Atlantic codfish. A constant dry wind in winter, with temperatures just above freezing, made it possible to dry the fish and store large quantities for longer periods. Stockfish was the food that enabled the Vikings to sail around the world more than a thousand years ago. It became vital for the Hanseatic economy and was the foundation of Norway’s economy and culture until oil and gas took over in the 1970s.

This old business and culture, all the international connections related to the many isolated islands far off the coast are what inspired Andreassen to create the pictures. These remote communities were not isolated, they connected people from different cultures, circulating food and money, as well as, Andreassen adds, stories and myths, happiness, dramas and changes around the world.

Are Andreassen, Gadus Morhua and Are Andreassen, Rosthjell, both 2018 © Courtesy the artist, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

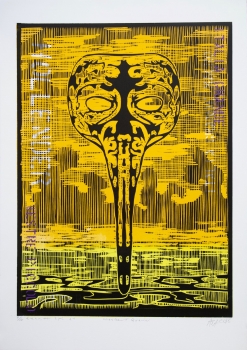

So the perspective broadens to include the striking silhouettes of the little neighbouring islands, for example, which were once very productive and where the people from Røst hunted and gathered the eggs of countless seabirds. Andreassen explains that there are now also far fewer herring gulls. And so it’s precisely this robust seabird which emerges in the form of a skull to form the pendant to the beak-shaped Masked Querini, which appears before the yellow of a signal flag indicating potential danger.

Are Andreassen, Maskert Querini, 2018 © Courtesy the artist, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

At least that’s how it was in Querini’s day, when ships sailing into their home ports were made to fly a yellow flag: perhaps they had the plague on board, brought in from who knows where in the world. Everything is connected with everything else, and wherever people conduct global trade and intervene in natural cycles, this becomes apparent. The motif has taken on a chilling new dimension through the COVID-19 pandemic.

Artists don’t always have an answer for the problems they draw to our attention, and they don’t have to. However, Andreassen does have a solution, and he didn’t have to spend long looking for it. People along the coasts have been talking about it since time immemorial – and not just in Norway. Many countries know the story of Utrøst, they just have a different name for it: they speak of a mysterious, invisible island that’s supposed to appear to shipwrecked sailors, saving them from drowning and certain death. It’s said that three cormorants, the princes of this island, lead the desperate sailors to land. Nature taketh, these lines tell us, and nature giveth back.

As I was talking with the artist about Utrøst, a certain old-fashioned sounding word came up – “humility.” I think what he meant was something like the notion currently being discussed in sociology under the term “uncontrollability”: it’s about accepting that we can’t control everything, that not every aspect of the world can be placed at our disposal and that our destinies are not entirely in our own hands. Perhaps we’re no longer so accustomed to this idea, but it’s a good one.

At the same time, Are Andreassen brings the theme of business and trade’s roles as vehicles of culture and communication into his prints to the extent that he emphasises their character as commodities and simultaneously provides them with a brand identity: as in the case of postage stamps or shipping crates, the woodcuts display brief passages of lettering along their edges. “Weste magro”, “Bremer” or “Italia grande” are terms used to define the quality of cod. The artist has used a stencil to add them: the orange, purple and ochre labels were inserted at the very end, while the white lettering is sometimes covered up by the impression from the black printing plate. In the traces of colour, which sometimes protrude beyond the images’ black frames, we find an expression of the small imperfections and handcrafted element that provide these works with their down-to-earth and very personal character.

For him, the fruitful encounter between the sailors under Pietro Querini and the inhabitants of the island of Røst is ultimately also a metaphor for how we ought to approach that which is foreign to us: with openness and curiosity.

Dr Pia Littmann, curator of the exhibition Steamers, Dykes, Dramas: Prints from the Collection and Contemporary Positions