Completely Immersed

There was so much to see and far more to tell: our colleague finally had to remind us that the museum would be closing in three minutes. We had entirely lost track of time, completely immersed in the past and the innumerable stories we had discovered and continued to discover – beautiful, surprising and thought-provoking. The photographs of Hamburg amateur photographer Fide Struck (1901–1985) were created during the period of transition between the Weimar Republic and the Nazi state. In many cases, the context behind their creation still remains obscure.

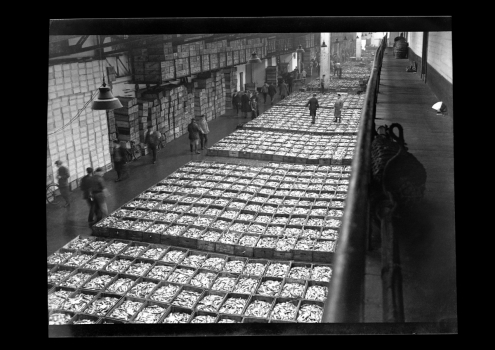

Fide Struck, Dock Workers Waiting for the Auction to Begin, c.1932

Razor-Sharp Focus

“It’s really unbelievable how razor sharp the focus in these photos is!” I heard this repeatedly during guided tours at the MKdW. I was struck by this again myself as we went through the exhibition Sailor Caps and Fine Threads – Fide Struck Photographs Worlds of Work along the Seashore, 1930−1933 just before Christmas. For example, there’s the group of dock workers at the very beginning: even in the last row, the faces of the men emerging from the darkness of the fish auction hall are quite recognisable. They’re talking, having a smoke. A man near the front has the stub of a cigarette tucked in the corner of his mouth and a little case sticking out of his breast pocket, presumably used to store his tobacco. We can read “Werschen-Weißenfelsen” on it, and “Braunkohle AG” must follow underneath his dungarees: this was the name of a mining company in Halle an der Saale that continued operating until 1940. Little discoveries like this can be made all over the place in Struck’s photos. Perhaps the young man had previously been a miner before he came to the waterfront. Now he’s in Altona working as a “Schauermann” – this German word for the dock workers responsible for loading and unloading ships comes from the Dutch verb “sjouwen”, meaning to haul or to toil. And that’s what the men are waiting for: the moment when things finally get going. They have a casual air and surely also want to look that way, perhaps they’re grinning a little more than usual – after all, it wasn’t every day they got their picture taken.

Work, Art and Reportage

The dock workers in the fish auction hall have taken up their poses. Fide Struck, who was in his early thirties, had formerly been a bookkeeper in Berlin and had been unemployed since the summer of 1932, sought contact but also chances to work more or less unseen: he captured the customs officer stepping on to the swaying ship filled with fresh fish, the dock workers packing eels, herring or plaice and then the fish crates lined up in the deserted hall. The reportage reaches its climax when we see the auctioneer, head raised and pointer in the air, gazing out past us at an angle. All the traders and restaurateurs surround him, and we once again find the dock workers standing there among them, this time as spectators. The image is bristling with suspense – a final bid is about to be accepted. Fide Struck is a wonderful storyteller.

Sometimes his interest in photographic experimentation shines through, and then everything suddenly becomes very objective and formally austere in the midst of all the bustle, people and faces. As a young man, Struck trained as a photographer at the Gildenhall estate for artists and artisans, which was a kind of early German commune located outside Neuruppin. There he lived and loved – especially the communist Else Großmann, which is a whole other story – and he also learned: from Curt Warnke, a photographer about whom little is currently known. Struck was shaped by this very progressive environment, and tendencies from the New Vision and other avant-garde photography of the 1920s and 1930s still continue to resonate in his visual idiom years later.

Fide Struck, Auctioneer with Pointer Used to Announce the Final Bid, c.1932

Fide Struck, Fish Crates, Each Containing 50 Kilograms, c.1932

Plate Edges

Fide Struck generally set out with a glass-plate camera. The motifs he captured in his photographs from the early 1930s – the fish or vegetable market, the smokehouse or the wharf – were caught on glass, not on celluloid. The reason why many of these images display oddly soft, wavy edges is that the plates’ light-sensitive film has become partially detached. The process is nonetheless fairly resilient: even now, after around 90 years, the glass negatives can still be used to create high-quality and also very large prints – luckily for the exhibition! Prior to printing, the images on the negatives had to be scanned and, where necessary, edited. After all, the photographic plates were preserved for a very long time under conditions that were not exactly optimal from a conservator’s perspective: we will come back to the trunk where they were stored later. Elke Schneider, photographer at the Altonaer Museum, accepted this laborious and complex task. Dirt on the glass or cracks and chips in it – working with this old photographic material demands a subtle, sensitive hand and patience as well as decisiveness. Determining whether the fissure in the left-hand corner or the spot near the top on the right underscores the picture’s historical character or simply represents a distraction is always a question of judgement.

In most cases, history wins: we’re allowed to and ought to see that the photos are old and have an eventful past behind them.

Plate camera (left) and roll-film camera (right), 1920s/1930s, on loan from Ane Ingwersen, Wyk, exhibition view at the MKdW, photo: Lukas Spörl

The Search for Clues

In 1942 Fide Struck packed his negatives in a trunk– a precondition of their surviving for posterity. Having endured the chaos of the war, undamaged by bombs and various relocations, the trunk passed into the hands of Struck’s youngest son Thomas in 2005. The younger Struck (b.1943) ignored the matter for a long time, presumably sensing how deeply engrossed he would become. It wasn’t until 2015 that he opened the trunk and became completely devoted to uncovering its story. Following an initial show at the Altonaer Museum in the Corona year 2020, the exhibition at the Museum Kunst der Westküste marks the second presentation of Fide Struck’s work as a photographer.

Ambushed by History

While preparing the exhibition it became apparent that Struck’s photo reportages had been printed in the newspaper Arbeit in Bild und Zeit (ABZ; Work in Image and Time) in October 1933. But the Nazis were already in power at that point. How could that be? No Nazi symbols can be seen in Struck’s photos and, based on everything we knew (and know) about him, he had an affinity for leftist ideas. And, on top of all that, worker photography was an idea of the left: Revolution from the bottom up! Overturning the conditions of ownership! And the working class that was supposed to achieve all this ought to be visible in the press. I felt like I’d been ambushed.

But how close together the extremes ultimately lay. We found out that the ABZ presented itself as the successor to the AIZ, the leftist Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (Worker’s Illustrated Newspaper). The latter had been among the most widely read papers of the Weimar Republic in the early 1930s. It offered serial novels, practical household tips and words of motivation for the working class, but it was centred around photo reportages: in keeping with the fundamental principle of communism, these displayed an international orientation and thus tended to focus on economic successes in other socialist countries or on the capitalist oppression of colonised regions.

The AIZ was confrontational, loud – and it adhered to a high artistic standard: the paper’s photographs were numerous and shot from bold perspectives. We can imagine that Fide Struck was also inspired by them and tried to get his own work published there.

When the Nazis put an end to freedom of the press in Germany, the editors of the AIZ emigrated to Prague. But the paper was apparently “too big to fail” back home and the Nazis’ sense of self-confidence was still fragile. With the help of a covert “succession”, they sought to discreetly and subtly familiarise workers who previously had an affinity for the German Communist Party with Nazi causes and concerns. At first glance, the ABZ could easily be mistaken for the AIZ, but the concept nonetheless failed to succeed. The newspaper would only remain in circulation until November 1993, the same month that the Nazis consolidated their power through a single-party Reichstag election. The catastrophe then took its course.

Means to an End

When I look at the men and women smiling at the photographer – and smiling at us, building a bridge into the present – I find it hard to make this connection, not to mention accept it. What did the networks and distribution channels for journalistic photos look like at that time? How exactly did Struck’s photos end up in the ABZ? Much will presumably remain obscure or in a grey area.

We’ll stick to the pictures for now. Fide Struck doesn’t depict heroically idealised workers, there are other images for that. But neither does he present poverty: the theme of precarious conditions appears only along the margins of his photos. Struck isn’t creating propaganda in any direction. In a period of political extremes, he lacks radicalism: that’s what makes his photos so good, so approachable – and so relatable. Thus, in the text surrounding his photos of the fish market and fish processing, the ABZ is able to extol a German economy finally gaining steam again. In no way can the vivacious character of Fide Struck’s photos, their extraordinary anecdotal quality and the photographer’s empathetic gaze be absorbed into this one-dimensional narrative: it’s as if they were leading a vibrant life of their own. Nonetheless, they were a means to an end. Unfortunately.

Fide Struck, Fish Auction: in the middle on the left the clerk in a light-coloured coat records transactions in his notebook, the auctioneer stands to his right in a dark suit and a woman in between them looks into the camera, detail, c.1932

Fide Struck, Fish Processing: Sellers and Customers along the Counter, c.1932

The evaluation and analysis of Fide Struck’s photographic oeuvre is still in progress.

Dr Pia Littmann, curator of the exhibition Sailor Caps and Fine Threads – Fide Struck Photographs Worlds of Work along the Seashore, 1930−1933

All reproductions of works in this article:

© bpk-Bildagentur – Fide Struck (Thomas Struck Coll.)

Links for Further Reading:

- Biography of Fide Struck

- Gildenhall Artisans’ Colony (in German), Museum Neuruppin (in German)

Television Reports:

- 25 Sept 2023, NDR Kultur – Das Journal (in German)

- 2 Oct 2023, Schleswig-Holstein Magazin (in German)

Inside the Exhibitions on YouTube:

- Digital tour of the exhibition at the Altonaer Museum (22 Jan 2020 to 14 June 2021) (in German)

- Einführung in die Ausstellung am Museum Kunst der Westküste (24.9.2023 bis 8.9.2024) (in German)