The place where I first came across Marie-Louise Exner’s prints was in a folder with image files – the photographs of her etchings lacked titles and were identified only by abbreviations. Exner’s pictures immediately spoke to me, but my original unfamiliarity with their titles presented riddles. What do we see when we don’t know what something is called?

One of the prints resembles a view of earth from outer space, where the cities glow brightly and rural regions remain dark. I later learned the Danish title – a language that I don’t know and which seems strange to me because its formal form of address is supposedly reserved solely for the queen, exclamation points are almost never used and its written form appears so different from how it’s spoken.

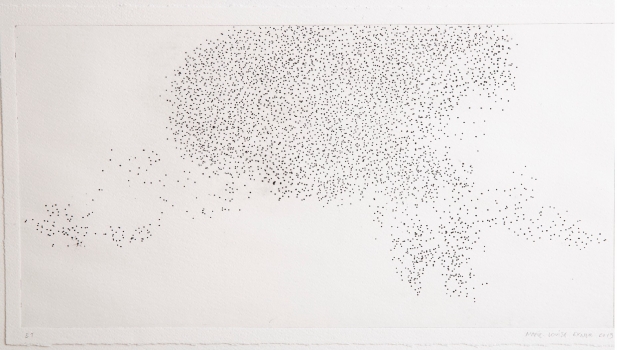

Sky af sorte stjerner is the etching’s name: Cloud of Black Stars. But the stars, stjerner, are actually starlings, stære. The riddle’s answer deviates somewhat from what I expected: Marie-Louise Exner has not chosen the view down from above but the view up from below, up into the sky where the birds are flying so close together that they form a cloud. Exner’s pictures radiate a sense of movement. The birds are arranging themselves into a new formation – and for anyone who, like me, sees the swarming birds as the dark points of light of major cities, they will appear to pulsate.

Marie-Louise Exner, Sky af sorte stjerner

By now Marie-Louise Exner’s works have arrived on Föhr and been safely placed in storage. I finally have the opportunity to look at these sheets in person. They’re big, much bigger than the images on my monitor. Viewing the originals also brings out the many shades between black and white as well as the interplay of thick and thin lines, wild scratches cut into the printing plate and mild-mannered hatching.

Nature over the Course of Time

My next encounter with Marie-Louise Exner is a telephone call. I ask her whether nature is usually or always the theme of her work. “It’s always nature, but it has increasingly developed into a consideration of nature over the course of time. I look back and I look forward. Besides that, I also think a lot about what it means to live in nature – because I live in it.”

At 25 the artist moved to the Danish North Sea island of Fanø. In addition to the landscape there, she’s particularly fascinated by the island’s musical tradition as well as the question of how people used to organise life “in the wilderness” in the past. Her artistic projects also include outdoor installations, such as the knitting of a tent.

If you search our online collection for Fanø, the name Exner immediately stands out. Marie-Louise Exner’s grandfather, Johan Julius Exner, also worked on the island. He painted rural life there in Denmark’s national romantic style. He also created many images presenting the beautiful traditional clothing of Fanø. “I think it’s funny that we walk around the same place,” says Marie-Louise Exner, “and that, for several successive generations, we’ve been interested in the same things. There are a great many differences between our work, but we walk through the same streets, the same nature.”

No Lookout Points, No Horizon Lines

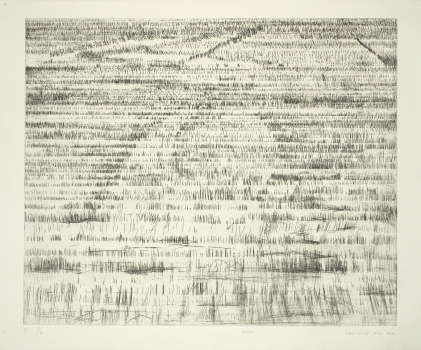

I tell her I was particularly drawn to a print I had “correctly” interpreted at first glance, even without knowing its title: Engen – Meadow. I felt like I was right there in the middle of it, lying in the slightly damp, evening-time grass of a summer meadow. What seems soft and inviting from a distance (the meadow) reveals itself up close to be a pointy and scratchy thing (the grass).

Marie-Louise Exner, Engen

Marie-Louise Exner explains to me that this is precisely what’s important to her: that, instead of just viewing her pictures like tourists at a lookout point, we’re right there in the middle of them. This is why, particularly in her works from Fanø, there are no horizon lines. “Fanø is one big world. The ebb and flow and everything happening in the sky and on the ground have such a hold on each other. I watch it all. I don’t divide the heavens from the earth.”

Even in those prints which seem to depict only the sky or the earth, we can still recognise interconnections. For example, Cloud of Black Starlings shows swarming birds, and these have to take off from as well as land in trees or fields in order to arrange themselves into a new formation in the air. In Meadow the wind has left its mark on the grass. Nature doesn’t allow itself to be enclosed within a frame: it continues to exist beyond the work.

Marie-Louise Exner’s answer to my question about what printmaking means to her also reflects this holistic attitude: “When we paint or draw, we start somewhere. In printmaking we’re working on an entire picture at once. Afterwards, details can be changed, another print can be made … That’s a wonderful, very meditative process in comparison to constantly creating and forming. It’s just your hands that are working; you’re talking with your technique.”

Pauline Reinhardt, M.A., PR & Marketing/Events